On The Cusp

A wali[1] once fell asleep on top of a hill. His sleep was deep and his dream vivid. In it, he found himself in a strange land, a place he had never been before. It was an empty place, devoid of nearly anything one would normally imagine there to be. There were no trees, no animals, no people, no buildings, no cars, just a narrow strip-like path that seemed to lead somewhere. So, the wali followed the path. He walked and walked through the emptiness, until he reached the mouth of a large cave. He decided to walk inside the cave and in there he saw thousands and thousands of people, maybe even more, all corralled together. There were men, women, and children, all of different ages, all wearing white robes, and all were jumping up and down, as though they were frantically trying to grab something from the air. The wali looked around the cave, which seemed to have no end, and stood in awe at the endless sea of people. The noise was deafening. But tucked away in one corner, far from the madding crowd, sat one old man by himself on a simple wooden chair. He didn’t seem bothered by all the commotion around him and so the wali went over to the old man to see if he could get some answers.

“Peace be onto you,” said the wali.

The old man sat up a little in his chair and with a warm smile replied, “and peace be to you.”

“Kind man, can you tell me, where we are here?” asked the wali.

“This here is purgatory,” explained the old man, “the waiting station for all those who have passed on from the mortal life and are awaiting the day of judgement.”

The old man said this in the most matter of fact way. He had long strands of hair, as white as the robe he wore, that flowed down from either side of his head and melted into his equally long and white beard. The wali considered his surroundings. He began to wonder about all the people that he had known in his lifetime that had passed away and who, according to the old man, must all be in the cave too.

“And why are these people all jumping up and down?” he asked.

“They are trying to catch the blessings that the angels sprinkle down on them. Don’t you see it? Don’t you see the angels up there and the blessings they dispense?” The old man pointed a gaunt finger towards the ceiling of the cave. “They fall like snowflakes blown from the snow tops of distant hills.”

The wali looked up but he couldn’t see the angels nor the blessings. As it were, he was still a mortal, unable to see the ethereal. All he could see was people jumping, some higher than others, grabbing at thin air. The old man could see the wali was confused so he continued to explain.

“When a person dies, and they come here to wait, they know that when judgement day comes, they will either go up to heaven or down to hell. But no one knows for sure where they will land. And so, in order to improve their chances for getting into heaven, people try to accumulate as many blessings of forgiveness as they can, which Allah graciously bestows on them, through the angels, until the day He summons all to Him.”

“If that is so,” asked the wali, “then why are you not among those that jump and reach for the blessings of forgiveness?”

“Ah,” said the old man smiling wryly, “I knew you would ask me that. You see, I am blessed in other ways. I have a son still among the living. He owns a small trade store where he sells all sorts of things. People come to buy from him because he is honest and fair. And all day long while he sells his goods to his customers, he recites the entire Quran beneath his breath in a quiet whisper. And as you know, dear wali, in Islam if you recite just one or two verses from the Quran for a deceased relative, then that relative receives countless blessings from Allah. So, you see, I don’t have to jump up and down for these extra blessings here. My son is already taking great care of me!”

The wali nodded at the old man and said, “You are a fortunate man to have such a thoughtful son. Truly you are bestowed with blessings.”

They sat together for a short while. The old man asked the wali many questions about the state of affairs in the world. Finally, when the wali got up to leave, the old man seized his hand.

“I must ask you for a favor, dear wali," said the old man earnestly. "When you go back to the living please look for my son. And when you find him, tell him that I am doing well, and tell him that I am thankful for his recitations which have brought me more blessings than I could have ever imagined.”

When the wali woke up from his dream, he remembered the old man and the promise he had made to him. So, the wali set off to the town where the son lived to pass on the message from the old man. He followed the old man’s directions and after several days of walking, he arrived in the town and found the little trade store. The store was run by a young man busy selling goods to a long line of happy customers. The wali found an empty spot where he wasn’t in the way and watched the young man serve the customers. They would tell him what they wanted, and he then walked to the back shelf to retrieve the requested items. And as he was doing this, the wali noticed something. He saw that the young man’s lips kept moving, almost incessantly, like the wings of a hummingbird. He tried to decipher what the young man was saying but his lips were moving too fast. When the line of customers had dwindled down, the wali walked up to the young man.

“Peace be with you,” said the young man. “What can I get for you?”

“Peace be with you, my son,” said the wali. “I am not here to buy something, I just want a a moment of your time.”

The young man put down a bag of dates he had finishing weighing for a customer and turned to the wali with courteous attention.

“I’ve been watching you for a while,” said the wali. And as you conduct your business, I see that you keep whispering to yourself. Tell me, what is it that you are saying?”

A little surprised at the stranger’s curiosity, but thinking no ill of it, the young man explained to the wali, “when you see my lips moving but hear no words, that is because I am reciting the holy Quran under my breath. I start from the beginning with Surah al-Fatihah and I continue until the end. And when I’ve recited the complete Quran, I say a brief prayer for my dead father before I start reciting it all over again.”

The wali realized that what the old man had said was true. Here was his son, a successful businessman, earning his keep well, all the while reciting the Quran and praying for his poor deceased father.

“I have a message for you,” said the old man. “In a dream I had the night before, I met your father. He told me all about you, where you live, where you work, and what you have been doing for him.”

The young man’s eyes grew big and he listened carefully to the words of the wali, for he missed his father dearly and longed to hear from him.

“Your father asked me to come and find you here and to tell you that he is doing well. He thanks you for your recitations, and he wants you to know that he is receiving blessings in abundance. Keep up the good work, my son.”

The young man was overjoyed with this news. He shook the wali’s hand and thanked him for coming all this way to bring him good news from his father. He gifted the wali a bag of exquisite dates, which the wali tried politely to decline but the young man’s insistence won out. The wali thanked the young man and went on his way.

It was many years later, when the wali happened to walk up the same hill again and having reached the top of it, felt tired and nodded off. He fell into a deep slumber and once more found himself in that strange and empty land. He followed the path to the cave, as he had done before. In it, he found masses of people still jumping up and down for God’s mercy. This time, the place was even more crowded than before. There was hardly any space left in the cave and the level of frenzy with which the people reached for the blessings had reached a fever pitch.

The wali had hoped to find his friend still sitting on his wooden chair. But the old man wasn’t where the wali saw him last. He searched corner after corner but couldn’t find the old man. Only the wooden chair on which the old man once sat on lay on its side in one corner. So, the wali went over to the chair, flipped it right-side up, and sat down for a brief respite. He watched the sea of people in front of him continue their ritual, as they had been doing for millennia, seeming never to tire. Suddenly his eyes fell upon a familiar figure in the crowd. An old, frail man with a long white beard jumping up and down just like the others grasping for blessings.

“But how could this be?” thought the wali. “The old man was heaped with blessings the last time I saw him. Now he’s among those asking for blessings. Surely his diligent son must still be reciting the Quran for his old father.”

Determined to find out what had happened, the wali went over to the old man and pulled him to one side.

“Old man, I’ve returned to see you in a miserable state,” said the wali. “Pray, do tell what caused this change in your condition.”

Struggling to catch his breath, the old man placed a hand on the wali’s shoulder and with saddened eyes confided in him, “oh wali, don’t you know? My dearest son who used to recite the Quran for me passed away last year. And now I have no one left among the living. So, as you see, I have no choice but to join the others in begging for blessings.”

And without delay, he returned to his appointed place and continued doing as the others did.

this month's feature story....

The Gift of Pronunciation

Have you ever wondered what it would be like if everyone you met could pronounce your name right off the bat? I have, on more occasions that I can count. In fact, the last time was probably just the other weekend. A good friend of mine invited me to a birthday dinner he had arranged at the Black-eyed Pea. It was a small, intimate affair of four good friends. When our waitress, Tabitha, came around to take our orders, my friend introduced everyone at the table. As he got to me, he stuttered a little, and instead of saying Rashid straight away, he said Rashad—a small mistake he makes from time to time when he gets flustered. He quickly realized his mistake and corrected it, followed by an ardent apology. Tabitha sensed an awkward moment and took it upon herself to lift our spirits by sharing a brief anecdote:

“You know, I once had a friend with a difficult name. No matter how hard I tried, I kept getting it wrong. Over and over, I butchered her name until one day my friend suggested, I simply call her ‘friend.’”

It seems there are few things in this world that are unique to you. Your physical appearance might be the first thing that comes to mind. Considering that there are over seven billion people living today, looking like no one else is quite a feat. Although, according to the doppelgänger effect, there is at least one other person out there who looks eerily similar to you. Celebrities get this all the time. Perhaps you’ve seen the photo of the African American man who looks just like a young Arnold Schwarzenegger but after a serious overdose of tanning serum.

The next thing most closely aligned with your identity would have to be your name. While you might not have a moniker that’s exclusive to you, within your sphere of influence you’re more likely to be the only one with it, especially if your name isn’t that ubiquitous. (Though, I once had a classmate from Nigeria, who had the misfortune of being called the exact same name as his father and his five other brothers.) A person’s name is like music to their ears; it’s their favorite word in any language. Granted, this might not always be the case; just think of all the famous people who’ve had their names changed: Reginal Kenneth Dwight simply doesn’t have the same ring as Elton John. Most people, however, hold onto their given names a whole lifetime, nurturing it like a delicate perennial. This becomes especially true if the name connotes something significant or corresponds with a preconceived expectation of who that person is to become. ‘Nomen est omen’—name is destiny.

As a rambunctious tyke, you yearn to hear your parents call out your name when it’s time for dinner. And, when you grow a little older and learn to read and write, you spend hours writing your name with a permanent marker all around the house—probably in another effort to make your parents call out your name some more, albeit in a harsher tone.

Since my older brother, Hirsi, had been named after a distant grandfather, tribal chief and caretaker of the coastal town Berbera, my parents decided to give their second child a strong Muslim name. Pronounced with an elongated rolling R (RrrAH-sheed), it consists of only two syllables. Its etymology is old Arabic and translates to the ‘rightly-guided.’ A derivative of one of the 99 names of Allah (God), Rashid, is an honorable name, and I’m proud it was bestowed upon me. Though, the dear Lord knows I do have a hard time living up to it.

From the age of about four or five, I’ve been answering to at least three different versions of my name. At home, I would hear the familiar "RrrAh-sheed" from my parents, siblings and immediate family. But, after starting kindergarten in Vienna, my name quickly took on a few new acoustic properties. Auntie Eva, my kind and pleasantly corpulent teacher, who had a penchant for serving sweet potato porridge every other day, decided to simply pharyngealize my name by converting the elongated rolling R into a glottal R, common to German and French. Here, the R sound is produced in the back of the throat by cupping the tongue around the fleshy appendage that hangs from the back of the palate called the uvula. Needless to say, this new gargling version of my name wasn’t too dapper, but instead of spending half my day correcting my toddler peers’ elocution, I adapted.

When I joined an International school years later, the first order of the day was to introduce myself to the class. I was determined to take an intractable attitude towards the correct pronunciation of my name, but as you might expect, it didn’t take long before the rolling R in my name metamorphosed once again—this time assuming an anglicized form, where the tongue never touches the roof of the mouth. This carried on into high school and college and then into my later life. Admittedly though, this adaption has always struck me as the most sonorous.

It hadn’t really occurred to me how prevalent this issue was among people with foreign or hard-to-pronounce names in Anglophone countries until I listened to a Cult of Pedagogy podcast about “how teachers pronounce student names, and why it matters.” As guests shared their experiences of what it was like to have their names mangled, the extent to which this could make a person feel less validated became quite telling given that efforts to correct a mispronunciation are often accompanied by a weary apprehension, or a fear of being a nuisance. Add to this a few other aspects of personal identity such as gender, ethnicity, and cultural guilt, and the complexities mount further.

Recent studies have even shown that a difficult-to-pronounce name can have an impact on employability. Inasmuch as pronounceability correlates directly to truthfulness of claims, people with easier to pronounce names are typically evaluated more favorably than their harder to pronounce counterparts.

Common courtesy in most cultures dictates that everyone deserves to have their name said right. They are gifted to us, usually at birth, and all efforts to maintain it must be lauded. But there comes a point when choosing whether to correct a mispronunciation or embrace it no longer becomes a dilemma, particularly if the deviation is slight. I, for one, have graciously accepted the many facets of my name, as though they were passports I carry with me when meandering through different cultures and languages. And, when I do engage with the few people that do know how to say my name right, hearing it then becomes that much sweeter.

Migrant Wave Recurs 20 Years After Hurricane Mitch

Heading north has always been an option for Central Americans, and their governments are generally reluctant to stop it. The much-needed money expatriates send home each year, to Honduras for instance, is the third largest source of foreign revenue for that nation. In El Salvador, it’s No 1.

Except what awaits those that take their chances in the land of opportunity is a string of clandestine, underpaid jobs and a life in fear of discovery by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Hardly the anticipated paradise, but at least they can make enough money to send home to feed their families.

Twenty years ago, a migrant wave from Honduras was expected to make its way to America in the wake of Hurricane Mitch. After pummeling the Central American region in October 1998, Mitch left about 10,000 dead and devastated the nations’ economies. While it did not receive as much media coverage as Sandy and Katrina, the death and destruction Mitch caused makes it the second-deadliest on record to hit the Western Hemisphere. At the time, Honduran President Carlos F. Facusse warned that a new wave of migrants would go walking, swimming and running up north unless other countries –especially the United States—help Central America get back on its feet. Because of the hurricane, the Clinton Administration granted 150,000 Hondurans and Nicaraguans living in the United States Temporary Protection Status (TPS)—the right to remain and work while their homelands recovered.

Today Hondurans aren’t running from a natural disaster. They are fed up of living in the most dangerous country without a declared war. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula, Honduras’ largest cities, have a combined homicide rate of 90.4 per 100,000, ranking them consistently among the top 10 world cities with the highest murder rates. The wreckage left behind by Hurricane Mitch and the lack of reconstruction thereafter is partly to blame for the violence and lawlessness today. That, and international drug cartels using the ravaged nation as a drug depot on the way to Mexico have exacerbated conditions further.

Government officials have long agreed that better living and working conditions in these countries would stem the flow heading north. In 2005, the U.S. House of Representatives signed in CAFTA, an expansion of NAFTA to five Central American countries (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Costa Rica and Nicaragua), and the Dominican Republic. Its purpose may be to expand regional opportunities for workers by eliminating tariffs and trade barriers, but since its inception, overall economic indicators for that region remain poor.

Does America Love Big Trouble?

“So, we got a little trouble ...” Linda Lee

“This is more than a little trouble!” Bruce Lee

“OK, so we got big troubles! You know you’re always going on about the beauties of your Chinese culture well let me tell you about the beauty of my culture: we love big trouble!” Linda Lee

It’s been 45 years since Bruce Lee’s death, and for the first time in years, I sense his popularity waning. To reacquaint myself with the life of this iconic American, who is also regarded as a national hero in China, I sat down to watch the biographical film Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story, released in 1993, on the 20th anniversary of Lee’s mysterious death. Many marveled at how, in a remarkably short life span, Lee managed to positively influence and empower many myriads of people around the world. One of Bruce Lee’s most admired attributes was his ability to overcome the endless social challenges as well as physical challengers he had to face.

As the fourth of five children, Lee was born in San Francisco, but his parents return with him to Hong Kong, where he became a child actor, often playing a provocateur. He stayed true to form well into his teen years, during which his indomitable personality would have him often skipping school to trade blows with the British boys in the colony. It was clear that prison was at the end of the road Bruce was traveling on. Determined to avoid this fate, his father pressed the birth certificate from the San Francisco hospital into his Bruce’s hand and told him to go seek his fortune in America. After a short gig as a waiter in a Chinese restaurant, Lee found his true calling in teaching martial arts. He enrolled at the University of Washington where he met his eventual wife, Linda, and together they swiftly opened a chain of dojos, first in Seattle, then in Oakland.

About half way into the movie, Linda and Bruce’s love is put to the test as they confront their first major obstacle in their young marriage. Because the other kung fu teachers in the Bay area resent Lee for teaching the secret craft to non-Chinese students and demand he stop, Lee, who believes he has the right to teach anyone who’s willing to learn, agrees to settle the issue through combat. But after decisively defeating his opponent, Lee makes the mistake of turning his back to walk away, giving his opponent the chance to deliver a dishonorably devastating flying kick. Lee finds himself laid up in a hospital bed, in the chiropractic ward, possibly paralyzed for life. As despair begins to dim the feeble flame of hope in him, his wife, Linda, refuses to give up without a fight and presents her powerful rebuttal: “OK, so we’ve got big troubles ... well, let me tell you about the beauties of my culture: we love big trouble!”

Long after the movie had finished, Linda’s words still lingered with me, and a series of thoughts struck me: Does America really love ‘big trouble?’ I mean, is it truly a nation that revels in having insurmountable problems—the solving of which would correspond to its strength of character as a nation?

The premise might seem ridiculous; for, who, in their right mind, would purposely want to have troubles? It can be safely surmised that most people—and nations for that matter—would try to avoid problems. Though despite this reflection, since its infancy, trouble, without a doubt, seems to always find America. Whether foreign or domestic, the struggles have been many; yet somehow, America manages to maneuver out of them, time and time again.

Now, what are some of the causes of this youthful nation’s predicaments? It may come as a shock to many, and some will even want to deny it, but America has an honesty problem. Despite the allusions to the contrary, it isn’t a secret any longer, that this country’s glorious past is riddled with disenfranchising untruths. From the time European settlers began populating the eastern coast, painstaking efforts have been made to propagate a narrative for this nation that, to a large extent, does not correspond with events as they truly happened.

Of course, America is not alone in this practice. In fact, most if not all great civilizations are guilty of manipulating their histories and commandeering the true narrative in order to meet their agendas. Sometimes the motive is not to embellish the past, but more rather to hide certain unsavory aspects of it. After the Second World War, for instance, Poland vehemently denied that any of its citizens aided the invading Nazi regime in murdering its Jewish citizens. In fact, a new law imposes a three-year prison term to anyone asserting that the Polish nation, or the Republic of Poland, was in any way responsible for the Nazi crimes carried out. This, even though overwhelming evidence suggests implicit, as well as, explicit collaboration with the invaders and their heinous scheme. By implementing this law, Poland is attempting to expunge a painful section from the annals of its past.

Australia is another young nation that has imbuing issues with its past. Similar to the United States, it too likes to begin its history with the arrival of the first European, the British sea captain, Sir James Cook; thereby taking little notice of the already present inhabitants, who, for the most part, had been living agreeably on the continent for millennia. Australia as a society is still so traumatized by its government’s treatment of the nation’s indigenous populations that it simply refuses to come to terms with the matter, creating a culture of steadfast denial.

In 2016, a document from the University of New South Wales containing an advisory list on terminologies to be used when referring to indigenous matters had the nation stirring. Conservative voices rallied and took exception at the document’s suggestions that Australia was not “settled” or “discovered” by the British, but more rather “invaded, occupied and colonized.” Whether stolen land or the stolen generations of indigenous people, the very thought of facing the realities of the past puts many Australians at unease. Denial is a powerful force in human psychology.

But when it comes to America there are two significant factors which make it unique, or rather rare in the league of nations: Firstly, America’s leading role in the fundamental values of democracy, and secondly, its diverse population and the pivotal role race has always played in the social, political, and economic infrastructure of American life. Nowhere else in the world—save, perhaps, South Africa—has there been a concerted governmental effort to subjugate, subdue and stymy those people who are of non-European descent. In the context of these two factors, the uncomplicated eye, the untainted mind clearly recognizes grievous hypocrisy. For where diversity ought to have been this country’s national treasure, it became the hidden underbelly of the vast American industrial vessel.

America’s distortions were already sown in the first chapter of its history books. 1492 and 1619 are two decisive years that are indelibly carved in the minds of anyone who attended a history class in the western hemisphere. By now, most people would agree that Christopher Columbus (whose non-anglicized name was Cristobal Colon, but that’s an entirely different kettle of fish) could not have discovered America in 1492, as legend has it, because native Americans, by that time, had already occupied vast tracts of it. Furthermore, Columbus certainly was not the first European to reach American shores. Leif Erikson, son of Erik the Red, beat the Italian to the punch by nearly five hundred years. The Norse king arrived on present day Newfoundland in 983 AD and established a settlement there. In fact, during Columbus’ four voyages, his ships made land in the Caribbean twice, Central America and South America. Until his dying day, the Italian navigator wasn’t aware that he had landed on a new continent (the Americas), insisting he had landed off the coast of Asia. All in all, Columbus was not entirely sure of his bearings and quite possibly never even set foot on the North American continent. Still, the myth prevails in print.

And it remains lamentable that young people, attending school or college, are taught very little about the integral part played by Africans in the earliest history of the “New World.” That, for example, two black explorers were among the first from the Old World to come to the North American continent—one, Estevanico, with a Spanish expedition, the other, Mathieu de Costa, as a guide for Samuel de Champlain in the Northern territories. Strong evidence suggests that Africans had participated in many of the first expeditions, with accounts of Africans facilitating Hernan Cortez in Mexico, Francisco Pizarro in Peru and Pedro de Alvarado in Ecuador.

Another significant figure in the discovery of the Americas was Pedro Alonso Nino. Despite being born in Palos de Moguer, Spain, he was of African descent, and an experienced navigator in his own right. Also known as “El Negro” (The black), he explored the coasts of Africa in his early days before joining Columbus to pilot one of his ships (possibly the Nina) in the 1492 expedition that brought them to mouths of the Orinoco River, in present day Venezuela. After returning to Spain, Nino resolved to return to the West Indies in search of the abundant gold and pearls the islands boasted, eventually returned home a wealthy man. (Unfortunately, a dispute with the Spanish King resulted in most of his bounty being confiscated. Nino passed away before the court passed its judgment on the matter.)

In an age when education and access to knowledge seemed limited, composing a preferred history with the stroke of a pen, became all too easy. Such was the case with the arrival of the first Africans in the United States. The first documented arrival of Africans in the colony of Virginia was recorded by John Rolfe, an early settler, who married Pocahontas, daughter of Powhatan, the local Native American leader. In 1619, Rolfe writes, “20 and odd Negroes” arrived off the coast of Virginia, where they were bought for “victualle” by the labor-hungry English colonists. The 20 Africans, along with other items of cargo, had been stolen by an English war ship, the “White Lion”, (and not by a Dutch warship as Rolf reported) from a Portuguese slave ship, and were brought to Jamestown. The ship’s captain was paid by the colonists for the Africans, who in turn required them to work off their “debt” as indentured servants. After a set period of time they gained their freedom, and later many owned lands alongside their English neighbors. But, as a result of Rolfe’s writings, countless scholars and teachers peg this date as the onset of slavery and the beginnings of African peoples in America, even though slavery, per se, did not emerge in the fledgling colonies until the late 1600s.

There is a body of general knowledge that educated Americans ought to be endowed with about African American contributions to the shaping of American culture, to the building of this nation. Alongside the works and genius of Eurocentric icons such as Shakespeare, Benjamin Franklin and Hemingway, other notable figures must be mentioned too. In this spirit, it would behoove all educators to take the time to put the spotlight on those brave souls whom history pages have left in the dark.

Whether science, literature, arts & entertainment, architecture, or sports, African Americans, with their inherent, yet bridled creativity, still changed the world. Perhaps names such Benjamin Bannecker who issued almanacs and helped survey the national capitol, and George Washington Carver, who derived hundreds of products from peanuts are commonly and rightfully known. What are perhaps less well-known are the inventions of slaves and free black men who lived much earlier. Elijah McCoy, the irrepressible African American inventor who coined the term, “the real McCoy” for his products on account of counterfeit manufacturers using his name for their inferior products, patented several lubricators for steam engines. Lewis H. Latimer (1848-1928), left behind a legacy of achievement and leadership that much of the world owes thanks. The sheer amount of inventions and successful patents secured by the Massachusetts native, ought to place him right next to the likes of Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Edison, with whom he broke ground on some of the most revolutionary inventions. Regrettably, history has only focused on one side of this mutual experience, leaving generations of young colored children thirsting for role models to emulate.

Dishonesty is intrinsically immoral. Everyone knows that. And whether profound or subtle, lies have consequences. However, in his sobering book, “The Liar in Your Life,” UMass psychology professor Robert S. Feldman asserts that two people getting acquainted, lie on average three times in a casual ten-minute conversation. And, although most of these lies are non-venal in nature, “mainly serving to make social interactions proceed more smoothly,” they create a feeding ground for more insidious means of deceit.

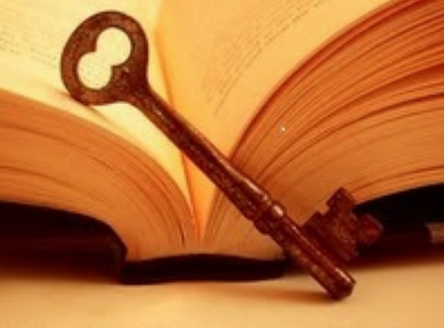

"Honesty," Plato wrote, "is for the most part less profitable than dishonesty." Upon examining America’s disinclination to adhere to the truth at times, we learn it has leaned on this tenet for far too long. When a government is just, honest and truthful, then its citizens are safe, secure and can prosper. But, for many, deceit holds the key to money, fame, revenge or power, and these prove all too tempting. Akin to the child that perpetually fibs, and seems to always get away with it, America is caught in a hardened habit, and hasn’t quite learned to be honest with itself. But if this nation, whose fundamentals are firmly planted in the evergreen soils of democracy, wants to be that what it ought to be, then it is high time for it to come clean and not fear the truth, which will inevitably produce uncomfortable consequences. After all, the true measure of America, and any other nation, will always be determined by how well it deals with the consequences of the truth.

The Bull Fight

The Bull Fight

A play by Rashid M. Mohamed

Characters:

- Porscha Klein, 44, daughter of deceased, and wife to Rudy Klein.

- Rudy Klein, 48, mediocre stock broker, got hitched into marrying Porscha.

- Lady Beatrice, 27, is an Icelandic environmental activist with a European accent and part heiress to Norman Child's fortune.

- Jorge Satillo, 53, is the Estate Executor

- Norman Childs, 78, deceased real estate tycoon.

Setting:

Office of the Executor, Mr. Jorge Satillo. Colorado Springs, CO.

The year, 2007.

Streaks of blue and orange line the sky over the rockies as both Porscha and Rudy sit in the Executors cramped office gazing out of the window. Next to the Executor’s desk stands an easel, with a covered painting. Anxiously awaiting Mr. Satillo, Porscha starts fiddling with Rudy's tie.

PORSCHA

Why did you have to wear the green one? You look like a UPS driver!

RUDY

Please don't start this again, dear. I know you like the blue one, but I spilled pea soup on it and it's still not back from the cleaners.

PORSCHA

(Scoffs at his remark) You and your damn pea soup! I swear it Rudiger, one of these days you'll be the death of me! (turning her attention, she points to the covered easel) That's got to be the painting! My beloved painting!

RUDY

Oh yeah, the famous Bullfight. You've been talking about that thing ever since we met. (Looks back out onto the snowcapped mountains, then turns to Porscha) Maybe we can go skiing when this is all over. Remember how much fun you said you had as kid, skiing with your Dad?

PORSCHA

Don't bring up daddy, you'll make me cry. (pretend sniff) I want to know what's taking so damn long. I already know what's in that will. Daddy told me a long time ago. So I don't see where the holdup is. (Edges closer towards the paining) Do you think I can take a quick peak?

RUDY

Now be patience, my little dove, I'm sure it’s just a matter of formalities. We'll soon be out of here with all that we expect and more. (he leans in for a kiss)

PORSCHA

(Evades the kiss) Careful, you'll smudge my make-up! Anyway, Daddy was a real man, a self-made millionaire. He never depended on anyone. Well, they sure don't make 'em like they used to!

RUDY

(Rudy whispers under his breath) Except for you ...

PORSCHA

(Snaps) What was that?

RUDY

(Shifts in his seat) Uh, nothing, dear. I was just saying, he depended only on you.

PORSCHA

Well, he had too! I was the only one around to take care of him when mom died. That's what good daughters do, you know. We can't all be mama's little nestling, like you were - some of us had to work hard!

RUDY

And a good daughter you were. Though your father really never liked me, no matter how hard I tried to please him.

PORSCHA

Now look, there's no need to sulk. I did choose you, didn't I?

RUDY

(Sighs heavily) I know, but sometimes I get the feeling you only did it to spite the old man.

PORSCHA

(Smiles wryly) Nonsense!

The door opens and in comes Mr. Satillo, a short man with a thick black mustache, followed by a strikingly beautiful tall, blonde woman wearing Chanel sunglasses. Rudy chokes as Porscha scowls.

Mr. Satillo

(With a Puerto Rican accent) Ah, Mr. and Mrs. Klein, I apologize for keeping you. Allow me to introduce. This is Lady Beatrice an acquaintance of the late Mr. Childs.

Porscha

(With scrutinizing eyes, up and down Lady Beatrice) Acquaintance? What kind of acquaintance? I've never heard of this person before. And why is she here today?

Mr. Satillo

(Clears his throat) Well, the law requires all parties mentioned in the Will to be present at this hearing. Lady Beatrice has been included in the will.

Porscha

That's impossible! I have a copy of my father's will. He drafted it many years ago, and there is no mention of an acquaintance! (directed at Lady Beatrice)

Mr. Satillo

Before we go any further, it is important for you to know that Mr. Childs prepared a last-minute Will which he sent to me. The courts approved it just weeks before his death. In that regard, any previous wills become null and void.

Porscha

What! How can this be! Why wasn't I notified? No, I won't accept this, I can't accept this. Rudiger, do something!

Rudy

(Stands up and with an air of authority bellows) What's the meaning of this, eh? Are you trying to double-cross us?

Mr. Satillo

(Visibly perturbed by the couple's outburst) No, no! Not at all! Please calm down, I assure you that all is in order.

(Everyone takes their seats, tension in the air is palpable. Porscha faces away from Lady Beatrice, her arms folded indignantly. Mr. Satillo calls his Secretary through the intercom on his desk. She walks in with Mr. Childs latest will, and a video tape).

Mr. Satillo

(Standing up he takes the bundle from the Secretary)

Thank you, Christine. Now, along with a new will, Mr. Childs also sent a recording of himself, explaining his final wishes. (He places the tape inside the old video recorder and the image of Mr. Childs pops up on the screen. Mr. Childs is sitting at his desk, flanked to his left by a gorgeous painting. It is the famous Bullfight by Francisco Goya. Porscha begins to whimper)

Mr. Childs

Alas, death comes to us all. At least I'm able to say what's on my mind before it's too late. For that I am eternally grateful. The last few years with cancer have been agonizing. Here I am a self-made millionaire with more money than I know what to do with but still, I can't buy back my health. Should have known all their years of drinking and smoking would come back to bite me in the ass. Well, now the hounds of cancer have sunk their fangs deep into me, and this time they're not letting go. (He coughs) For all its worth, I'm ready. Ready to depart this wretched excuse of an existence. Let's see what the next chapter holds for old Norman. And as for you, my loved ones (he gives out a loud sarcastic hah! followed by deep coughing) I have only this to say: Where the fuck have you been!? Porscha, didn't I always treat you like my darling princess? Why didn't I hear from you? Once you married that good for nothing punk Rudy, you disappeared out of my life like a snitch taken into the witness protection program. Are you still with that loser? Is he here, hmmm? (Piers closer into the camera, as if scanning the room)

Rudy

I'm here, you old fart bag!

Porscha

Shut up, Rudiger! Don't talk to daddy like that!

Rudy

I can talk to him any way I want now, he's fucking dead!

Porscha

Don't say that! He might could hear you!

Mr. Childs

(continues to talk) anyway, I don't give a rat’s ass if that mama's boy is still hanging off your coattail. Eighteen years ago, when you brought that son of a bitch home to me and said, ‘Daddy, I'm gonna marry him,' I knew I'd never see you again. Not one visit in the last fifteen years. Well, as far as I'm concerned, the two of you deserve each other. That's why I've decided to donate 60 percent of my fortune to a fund that helps improve inner city schooling. I'm tired of seeing poor kids not getting a descent education and eating garbage for lunch every day. The remaining 40 percent will go to my pride and joy, Lady Beatrice. That's right, take a good look. She's been here for me during my darkest hours, and she's gonna make something of herself. I'm gonna invest in her future. As for you two, I suspect you've been doing fine without me, since you stayed away all this time. I guess that trust fund I set up for you upon your marriage has kept you plenty fed, enough to keep you from coming back. Therefore, you don't need my help. Oh yeah, and another thing, I don't want a funeral or some dumb burning ritual. I want to be cryogenically frozen, so I can come back in the future, when things aren't as fucked up! So long, suckers! (Video ends with image of father frozen on screen)

Porscha

I can't believe daddy would do this to me! (Places wrist on forehead) Oh, I think I'm gonna faint! (Rudy holds onto his wobbly wife)

Mr. Satillo

We have lots to go over, I suggest we begin. In essence Mr. Childs has laid out his wishes quite clearly in his will and in the video. He ... (is interrupted by Porscha)

Porscha

I wish to contest this will! This is a scam and I won't stand for it!

Mr. Satillo

Mrs. Klein, it is within in your full right to contest this will, however I must appeal to your finer sense of judgment to first allow me to exercise my honorary duty as Executor of the Estate and proceed with the hearing.

Porscha

Yeah, yeah, whatever! I don't see why I should sit through this farce!

Lady Beatrice

(With a curt, but endearing European accent) Well, you are welcome to leave. I mean, seeing as you're not getting anything, why hang around?

Porscha

(With a harsh stare) Look at that, Barbie can speak! Oh you would like that, wouldn't you? Well, I'm not going to give some blonde hussy the satisfaction of making off with my father's estate, without a fight. What were you doing for him anyhow? Oh wait, let me guess, what you Europeans do best! (puckers her lips and bobs her head like a chicken – Rudy cracks up uncontrollably)

Mr. Satillo

Ladies please! I implore you to stay civil in this matter out of respect for the deceased. Let us proceed.

Lady Beatrice

(Turns to Porscha) Mr. Childs was always a gentleman in my presence. He was like a father figure to me.

Rudy

(Starring at her long legs, with a broad smile whispers aloud) I'd like to be your father figure ...

Porscha

(With a stern look) Rudiger! How dare you!

Rudy

(Cowers back in his chair) Oh, I'm sorry dear, did I say that out loud?

Mr. Satillo

We really must move on. Now, since Mr. Childs liquidated all his assets, including the mansion, the cars and holdings, there remains only one item for discussion; perhaps the most valuable item Mr. Child possessed.

(Walks over to the easel and removes the linen covering, to reveal the Bullfight painting)

This invaluable painting, appraised at $16 million was not mentioned in the will nor in the video by Mr. Childs. (Pointing at the frozen TV screen) You can see the painting beside Mr. Childs, denoting not only its monetary value but more so its sentimental value. The question therefore begs, why did Mr. Childs not designate this priceless piece to anyone? According to the law, Lady Beatrice would inherit the painting along with the remaining 40 percent of the estate.

Porscha

Wait a minute, she gets everything? The money and the painting? That's not right! Oh, hell no! (she pulls out a nail file from her bag and rushes to the vulnerable painting, brandishing the weapon) Stand back! I swear it, I'll tear the torero a new asshole! I don't care!

(Jaws drop, as everyone freezes in their stance)

Mr. Satillo

Mrs. Klein! Do you have any idea what the ramifications of such an action would be? Why, you'd be looking at a long jail sentence! So please, be sensible, put the weapon down!

Rudy

(Edging carefully closer to his wife) He's right my dear, don't do anything foolish! Nothing has been decided yet!

Porscha

Foolish? I'm being foolish?! After all that I did for him, this bitch is gonna get it all? We'll see about that!

(She raises her arm about to strike at the painting but pauses long enough for Rudy to grab her. She collapses in his arms, he sits her back down. Mr. Satillo rushes over to cover the painting again)

Lady Beatrice

If you love the painting so much, how can you want to destroy it?

Porscha

(Dramatically exhausted, wipes her brow) Oh, what do you know, Charlie's Angel? I cherish that painting! Ever since daddy brought it back that summer from his trip to Barcelona, I knew I had to have it. Mom loved it too. Whenever the two of them starred at it hanging over the fireplace in the den, well, that's the happiest I remember seeing them. Standing side by side in front of the crackling fire. Sometimes not saying anything but just gazing at the brave torero and the raging bull. I used to wonder what they were thinking. Were they the same thoughts separated by matter or were they different thoughts feeding off one another? I never wondered for long though because all I cared about was seeing them together. I love that painting, I could never destroy it!

(sobs, now directs monologue at frozen screen of her father)

It wasn't easy for me neither, dad! When mom died, I was only twelve, for Christ's sake! Cooking meals, doing house chores, keeping up appearances. I wasn't mom! Instead of hanging out with my friends, you had me locked up in that ivory tower, like Rapunzel, bursting to break free. Oh, how often I dreamed of running away, away from Pine Grove, away from all the chores, away from you! I dreamed of thumbing it to sunny San Diego and hanging out with Donny from the Beach Boys. I was going to marry him, you know. And when I finally got my chance, I made sure I'd be as far away from you as possible. But in vain I ran, in vain, for your grip never loosened. Even at College you'd visit unexpectedly and hover around my dorm, like the looming shadow of a red hawk, and I, the anxious squirrel. Can't you see dad, you never ever let be breathe! Just because you lost mom didn't mean you'd lose me! There was no reason to suffocate me! Even now, beyond the grave, you're still sucking all the air out of me!

Rudy

(Consoles his wife) Oh darling, don't get all worked up. Remember what the doctor said!

Lady Beatrice

My father was a sperm donor. That's all I know of him, that's all my mother knew of him. Sample number 7376, apparently very popular in Reykjavik. That's why I never dated in my hometown, the chances I was sleeping with my half-brother were too high. (cute giggle)

I met Mr. Childs, Norman, at a fundraiser where I gave a speech on how climate change is affecting Iceland. He was very moved by my passion and asked me out to dinner that same evening. We stayed in touch, he called me every week to make sure I was alright. I appreciated that very much. You see I was lonely here in America and Norman filled that void. We'd go to theatre plays and the latest art exhibitions. We both loved art, and he taught me so much. (pauses to think) Did you know Goya was the official court painter, and was literally exiled from Spain at the ripe age of 78; deaf and penniless? (Shakes her head) I really learned a lot from him and I guess I saw in him the father that I never had, and he saw in me the daughter he had lost. (Pause) Porscha, you must know, your father did love you.

Porscha

Oh really? Is that why he's given the family fortune away to a practical stranger?

Lady Beatrice

(Smiles and leans in closer) I wasn't a stranger to him, Porscha. We got very close in the three years we knew each other. We made each other happy. (She reaches into her purse and pulls out pictures from a pocketbook)

Here we are at the Grand Canyon. Oh, and this was when we took a road trip out to lake Tahoe. We really had a good time together when the pain wasn't bringing him down. Here's one of us at my Doctoral Hooding Ceremony.

Porscha

(Subdued) Daddy was a good man. (Sniffles) He just needed someone to be there for him. I guess I'm glad it was you.

Lady Beatrice

(She moves her chair closer to Porscha and places one hand over hers)

Porscha, before your father died he asked me to promise him one thing: That I would give you the painting. (Porscha's eyes widen) You see, although he was greatly upset that you never came to visit, he could never begrudge you the one thing that you had always cherished. He reminisced a lot about the young family he had, and how the painting belonged to those happier days. Believe me he wanted you to have it, he just wanted to make you sweat a little for it. That's why he never mentioned it in the will. Your father loved a good old bullfight!

Porscha

(The ladies embrace) I think this will be the beginning of a long-lasting friendship. Shall we go for a little walk?

(They get up chatting, and walk out of the office without a word to the men)

Rudy

(Rudy turns over to Mr. Satillo with a sigh of relief) have you got any liquor in here? I think they'll be a while.

Mr. Satillo

(Smiles) Yes, this calls for a fiesta!

(walks over to a cabinet, retrieves two shot glasses and a bottle of Jose Cuervo. On his way back, he turns off the T.V. and the frozen image of Mr. Childs disappears from the screen).

******

The End

Beneath it All

Cuangar must be the strangest town in Africa, thought Okone as he lay on a lumpy straw mattress, in a chalky bed and breakfast that peered out west, onto the congruent jawline of Namibia’s skeleton coast. The five-hour drive from Windhoek was bumpy and had worn him out. It wasn’t in his nature to wonder far beyond the capital, where he spent his time as a quasi-archeologist digging up ruins from the ancient city of Silwa, on which Portuguese colonialists heedlessly built their city, Windhoek. Centuries of sand dunes had kept the primeval Kho khoi settlement hidden, but a new wind blew in from the North, and it slowly roused the days of old.

Okone couldn’t remember the last time his efforts brought forth any noteworthy finds. His father had wished for his only son to become a dignified physician, the kind that flies in nifty little airplanes across Africa, healing the sick and saving lives. “There’s good money in being a doctor,” his father would say. Instead, Okone quietly pursued his love for digging up old stuff, unveiling the past, forever after that significant discovery that would make everything fall into place.

In Cuangar it rained all the time but still, the land stayed dry and thirsty, like a tropical desert. Dust was everywhere. It covered the shingled rooftops of the small shotgun huts, it got into the eyes and ears of the people, and it got into the cracks and crevasses of the patchy roads last paved by the Portuguese. Then when it rained, the dust turned into gooey muck that oozed out of people’s ears and dripped down the slanted rooftops like fresh pigeon poop. Okone kept a damp handkerchief on him at all times, afraid the dust and goo might shut his eyes closed if he wasn’t careful. It happened all the time. Children in Cuangar would go to sleep forgetting to cover their eyes with damp cotton goggles and when they woke up the next morning, dust and rain had cemented their eyes shut.

Okone ran the thin edge of his wet handkerchief across his eyelids and over his eyelashes for the twentieth time that afternoon. His off-white safari suit now layered in a film of powdered dust from the mattress looked wrinkled, but he didn’t mind so long as his skin didn’t absorb the microscopic grime that left no smidgen clean. Light footsteps along the creaky floorboards of the corridor stopped in front of his door, leaving a shadow visible through the floor gap. After a short pause came a weightless, enigmatic rap at the door that sounded like morse code.

Okone rose with difficulty from the bed and straightened out his old safari suit as best he could, before tugging the door open. The old man standing in the empty corridor was tiny, barely four feet and wore a wide-brimmed Panama hat that half covered his barren face. Clothed in a stiff polyester suit, that didn’t quite hide the sweat patch across his narrow chest, he stared curiously at the tired, unkempt young man across the door sill, with a certain familiarity; like the scrutinizing gaze of a long lost relative.

“Keeping your clothes ironed repels the dust, you know,” remarked the old man, pointing a carved wooden cane at the young man’s pant legs. Okone’s face began to tingle and warm up like a chided schoolboy’s. Wiping the embarrassment from his face with the damp handkerchief, he stepped back to allow the guest to enter.

“Please, do come in,” said Okone.

“You are Dr. Okone Mandiba, renown archeologist, aren’t you?” asked the old man, taking careful steps to avoid the dust mounds on the floor. His fine Italian leather loafers were draped in opaque plastic shoe covers.

“Not sure about renowned,” replied Okone, pulling out a wooden chair from beneath the writing desk and offered it to his eccentric guest, who, with the wave of a wrist declined it.

“Thank you for taking the time to see me,” said the old man. The situation is delicate and I need the best man for the job.” The old man’s face looked much older than the rest of him. Okone couldn’t help gauge his age. His voice sounded like church bell chimes, melodic and everlasting.

“Well, I’ve been thinking about our conversation and honestly, I can’t make much sense of it,” said Okone shutting the door before more dust flew in from the uncarpeted corridor.

He was still unsure why the old, eccentric man called him out to this bizarre town. The two men stood face to face in the middle of the room in a stiff stance, like two African statues mimicking one another. Finally, the old man broke the silence.

“They tell me you are the finder of lost treasures. Well, my albino kitten, not yet six months, has run off and I need you to find her.”

Okone could hear his father’s weighty words bearing down on him from afar: “What, after all that education, you have now become a pet detective?”

“I’m an archeologist, I don’t do lost pets,” replied Okone.

“Ah, but I assure you it will be worth your while,” reciprocated the old man with a convincing smile.

“I suggest we get going right away, it’ll be dark by the time we get there, we haven’t any time to lose,” said the old man.

The sudden urgency caught Okone by surprise. A surge of energy galvanized through his veins, dissipating any previous apathy. Scanning the room with hawk-like precision, he honed in on his rucksack and an old vintage World War II flashlight that served as a paper weight on the desk beside the door. He grabbed the torch, stuffed it into his bag then reached for the door.

“After you,” he said, gesturing to his guest.

The old man owned a large piece of land on the edge of Cuangar, where the myriad of trees and grass were lush and evergreen, feed by a rushing stream. Driving through the conservatory, Okone marveled at the lack of dust and the fertile fields and thought this must be what the Garden of Eden looked like.

“How is it that all of Cuangar is suffering from a drought and your land stands out like an emerald in a dust bowl?” asked Okone bewildered.

The old man smiled without looking away from the road. His eyes barely reached over the large steering wheel of his Ford Fairlane convertible, and his wrinkled cheeks reminded Okone of the concentric rings of an old baobab tree that told the story of time.

They drove up to a small cave that dug down along the side of two mounded hills that resembled the budding bosoms of a young girl. The Khoi khoi call them ‘Naso Hablood.’ The old man switched off the engine and turned to Okone.

“The kitten tracks lead up into the cave,” said the old man pointing his cane at the wide opening.

“All you must do is go in there and bring her back to light.”

Okone clutched his rucksack and pulled out his flashlight. He switched it on and off to make sure it worked and stepped out of the convertible. The old man followed him to the mouth of the cave.

“Remember, the kitten is still young and easily frightened, so tread lightly,” he said before Okone stepped into the dark cave kindled by his dim torch.

The cave was more wide and shallow than it was deep, with smooth rounded walls that reminded Okone of the ancient royal burial tombs in the ruins of Silwa. He turned his light toward every darkened corner and called out for the feline in a soft voice. He ventured further into the low lying cave but there was no sign of a living creature inside. Bewildered at the task, he wiped the sweat from his cheek before it ran into his mouth and sat down on a large rock in the middle of the cave, placing his flashlight carefully next to him. Where the light shone onto the polished wall, Okone could make out the faint outline of a drawing that resembled a white leopard. He clutched his flashlight and moved closer to the sketching. Though time had faded some of the bright colorings, the large rendering of a leopard was still very vivid; crouching, ready to pounce. Beneath the menacing leopard, as if guarded by the formidable beast, Okone found a small mound of round stones heaped up next to the wall. Carefully, he removed each stone, one by one, only to uncover the skeletal remains of a tiny toddler, wearing royal garments, still fisting an intricately sculpted ivory leopard, with shimmering emerald eyes.

He eased the boy’s centuries-old grip and held the exquisite animal in the beam of his flashlight, marveling at the intricate artistry. What incredible fortune! When he’d had his fill, Okone carefully placed each burial stone back with much consideration, then scrambled out of the cave, flashlight in one hand, artifact in the other. Outside, he found the old man standing next to his convertible, leaning on his wooden carved cane, smiling placidly from beneath his billowing Panama hat.

“Every man is destined to find that what seeks him,” said the old man.

With dancing eyes Okone smiled back at his benefactor then pulled out his handkerchief and wiped away the dust of time from the ivory leopard.

"Every man is destined to find that what seeks him."

Ode to Blank Paper

Eternal canvas,

spread

like ironed linen

on a starched wedding

night

moonlit.

You live where dreams

shine out

the chasing hounds,

where castles breathe

again

and where arthurian knights

battle

for wide eyed maidens.

You are flat

like the old world

undiscovered,

like rice cake

withholding

flavor

you tease away

salt and sugar

as the peppered quill

awaits,

as

grey ideas

guide

trembling hands

across your landscape

in search of everlasting serendipity.

Alas, Life!

Virgin births

of illiterate suns,

pure

celestial words

from the aspen seed

that spawned your pulp

with promise of print.

Calligraphy

blunt and clumsy

at first,

the pen taunts

your lukewarm embrace

a drop of ink

drowns,

in your

rectangular bleach pool

gasping

for essence

your victim

caught,

between

blue parallel waves:

Write! Write!

Your voice

siren-like,

white noise

urging

confessions vaulted

beneath

dusty lies,

enticing

Michelangelo’s cherubs

blessed

with the genius

of Latin,

to draw hieroglyphs

on flaky papyrus,

to unfasten

Elysian fields

of fallen

poets

and scribes

who guide

faithful pilgrim

over

calm rivers

and

tempestuous brainstorms.

Knowledge Without Borders

In light of the immigration debacle, currently yanking at the social fabric of this nation, I asked a good friend whether I should publish my experience on the topic. His response was: "Go for it - this isn't the time to be timid."

-----------------------------------

I’m excited to be on a plane again. That feeling of not knowing what to expect of a new place is a sensation I share with all the great explorers, from Magellan to Vasco da Gama, as they traversed the seven seas in search of new adventure. A new millennium is upon us and I am Sindbad the sailor on my second voyage to the Americas.

When I graduated from high school in Vienna six years earlier, I had big plans of studying medicine at one of Canada’s premier academic institutions: the University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario. I applied to many Universities both in Canada and in the US, but receiving the acceptance letter from Western is indelibly engraved in my memory as one of my fondest.

Most of my classmates had been accepted to their school of choice, so we leisurely enjoyed our graduation trip to the Canary Island – a Spanish archipelago just off the west coast of Africa. Knowing we wouldn’t see each other for a semester or two, we made the most of our trip; hurtling across desert dunes on our cheaply rented motor-cross bikes during the day, then getting down at the ‘Chica Boom Room’ into the wee hours of the morning. Forty rambunctious graduates with no parent or teachers to reign us in; living on staples like baked beans, scrambled eggs, and a liquid diet of tequila and Heineken. I lost 20 pounds in two weeks – but it was worth it.

A month before College would begin, I sought out the Canadian Embassy in Vienna to apply for a student visa. Posted a hop and a skip away from the American Embassy, I strode into my interview confident — answering all questions honestly and to the best of my ability.

Two weeks later I was notified by letter that my application for a student visa was denied on the grounds of my nationality. I was gutted.

At the time, I held a Somali passport.

Still caught in the throes of civil war, Somalia often conjured unpleasant memories of ‘Operation Restore Hope‘ and frightened special-operations pilot Michael Durant, who was captured after his Black-hawk crashed onto the streets of Mogadishu. While thousands of Somalis sought refuge across the globe, many headed to the immigrant-friendly cities of Canada, until that country had its fill.

Furious that I could be considered a potential refugee, my father arranged for a meeting with the Canadian Ambassador in Vienna. As a senior ranking diplomatic officer, he didn’t need the Canadian government to worry I’d become a financial burden on them. Yet, however much the apologetic Ambassador expounded, his hands were ultimately tied on the matter--the issue had become national policy. So, upon leaving the Embassy, my pragmatic father turned to me and said, “Never mind son; choose a US college instead.”

In the end, I became a proud Bobcat at Ohio University, graduating with a Political Science degree.

And as a restless young man, America provided me with the conditions I needed to find myself; for that I will always be indebted to her. Later on, I never gave much thought to the ‘Canada incident’ again, except for when I would cross the Detroit- Windsor border in a Greyhound bus to visit my aunt in Ottawa.

Crossing the vast Atlantic again, I try to envision my life in Florida, the Sunshine State. Will I be able to concentrate on my studies with the sun and the beach beckoning right next door? On the cover of the Time Magazine, sprawled face down across my lap, is a portrait painting of Bush II–and the caption reads ‘American Revolutionary.’ I remember that a colleague and good friend of my late father owns a house not too far from Tampa.

My eyes try to spot waves on the blurry ocean below as my mind wonders to the countless bodies that lay, at one time or another, on the ocean ground. Bodies that were tossed aboard by slave merchants, when they miscalculated food rations or when slaves became sick and died. They say one-third never made the perilous voyage across the middle passage, that corridor of hell from Africa to the Americas.

I think of my father with whom I hatched out this plan, who passed away just weeks before my intended travel. Naturally, I postponed my trip by a semester. I remind myself that I’m doing this for the both of us.

My stomach clenches at the thought of my mother recuperating from a heart condition and who refused to let me reschedule my trip once more. Lyrics from Tupac’s “Dear Mama” burrowed their way into my subconscious:

… and there’s no way I can pay you back,

But the plan is to show you that I understand. You are appreciated.

The first rays of the east sun soon pierce through half open window shutters and flight attendants start handing out customs and declaration forms.

We arrive at Newark Airport on a muggy weekend morning in July. Weary passengers try to form orderly lines in the arrivals section, according to their status: US Citizens, EU citizens, and the rest of the world. After the Canada incident a few years back, my passport now reads European Union, Republic of Austria. I’m good. . . so I think.

Why is it that immigration officers are the same wherever you go?

Somewhere, far in the Siberian outback, behind the Ural mountains, must be a special academy that teaches immigration officers — regardless of their nationality, gender or race — to be the most unfriendly souls imaginable. A place where they're made to complete a course that’s administered during six months of soul-hardening winter.

The young, stern-looking immigration officer wears her hair tied back so that the tip barely touched the collar of her crisp white uniform.

“Passport.”

I hand over my travel documents.

“What is the nature of your travel?”

“I’m here to attend graduate school.”

“University documents.”

I hand her my I-20 Form — a document verifying an international student’s acceptance — with my eyes glued to her pigtail, which bobs up and down as she glances from the I-20 to her computer screen. Behind her, I watch relieved passengers who’ve successfully passed purgatory pick up their luggage.

“Where’s the stamp from the school?” she asks, her eyes meeting mine for the first time. I look down at my document and see next to the signature in small print the words: ‘School stamp here.’ But there is no stamp. There is a nice big signature that makes it look official, but there’s no stamp from the school.

“The stamp is missing,” she reiterates in a tone that almost sounds final and before I can summon a response, she hails an officer standing at the back and hands him my passport and documents.

“Follow him.” Her last words.

“Follow him where? I got a connecting flight to Tampa in less than an hour.” The agitation in my voice was clear, even to me.

“Sir, please come this way,” says the new immigration officer curtly.

My legs still wobbly from the nine-hour flight, I try hard to keep up with his long strides that eventually bring us to the Immigration and Naturalization office. Seated on uncomfortable chairs, all donning long faces, I find half a dozen other passengers awaiting their fate in limbo. The quick-footed officer hands my documents to the officer behind the counter, before telling me to have a seat and wait until I’m called up. A cold blanket of powerlessness drapes over me as he disappears and the minute hand on my Swatch ticks nearer and nearer to my flight’s departure time.

“I’ve got a connecting flight here in less than thirty minutes. How long will this take?”

“Sir, just take a seat. Doesn’t look like you’ll be on that flight.”

Indignant at his tone, I plead my case further.

“Look, classes begin on Monday; I’ve got to be on this flight.”

The lanky immigration officer’s thick mustache begins to twitch. I watch him rise up to his full six and a half feet — a golden crucifix caught in the collar of his white undershirt.

“Don’t you know, we are at war with you!” he bellows, strong Latin accent betraying his own story of immigration.

The weight of his words feels like a noose tightening around my throat.

Anger effervesces inside, as his accusatory gaze made me soon realize that this time the issue isn’t my nationality, but my religion.

Another officer, more senior and adept at handling the volatile situation, steps up to the counter and attempts a more diplomatic approach.

“It looks like you’re missing an integral part of your document, without which we cannot let you enter the country. You must know, we now have a zero-tolerance policy after 9/11.”

“But the rest of my documents are in order, as you can see – signature, visa, etc. Surely, it must be possible for me to have the school stamp the I-20 upon my arrival. I assure you, I’ll fax it over. This isn’t my first time in the US.”

“No, that might have been possible in the past but we now have a zero-tolerance policy after September 11.”

With the familiar tone of finality resonating in his repeated words, I take the last opportunity to contact the University in Florida. But it’s Saturday and I only get the Admission’s office mailbox. Walking back over to his side of the counter, the officer gathers my documents and explains, “You’ll just have to go back and get your paperwork in order.”

Within the hour, I’m fingerprinted, documented and put on the same airplane — which had been refueling during my ordeal — back across the waves again. A film of grime and shame sticks to me like saran-wrap.

The flight is full again and I find myself next to Father Christmas. A short, round man with curly white locks that jut out from above his ears and a thick white beard to match. His rosy cheeks and the thin spectacles balancing on his nose as he reads from a pocket-size Bible adds to the authenticity.

“Are you alright?” he asks, setting down his Bible.

The million thoughts in my mind are manifested through my restless leg and the half-eaten Hot Pocket on my lunch tray. The words ‘stamp’ and ‘at war with you’ ricochet between my temples like canon balls on a battlefield.

One glance at the old man is all it takes for me to unburden my soul. He listens intently — as only a man of the cloth could — while I tell him my story, from beginning to end.

“I don’t believe in coincidences,” he finally says.

“You see, I’m traveling with my wife,” he points towards a row of seats ahead of us. “She’s sitting up there somewhere. They gave us separate seats at the airline counter, for some reason. I thought it was a mistake, but I know, God doesn’t make mistakes.”

The situation was truly more than serendipitous.

“There’s a reason why you’re going through this hardship, and there’s a reason why we met. Relief will come soon, my son; let us pray together.”

Drowning out the snoring passengers, this pastor from Gary, Indiana, on his way to a convention in Rome, soothes my tormented soul by reading verses from his Bible — condensing the nine-hour flight to what felt shorter than the blink of an angel. Feeling light and purified, like white foam on ocean waves, we part ways at Charles de Gaulle airport; he and his wife off to Rome, and I to find a payphone.

“Mom,”

“Yes?”

“Small setback. . . I’m coming home.”

“Oh, thank God.”

Those three unexpected words — from my mother’s still fragile voice, knowing she still needs me there — shower me with relief and reassurance:

God doesn’t make mistakes.

Education and true knowledge aren’t bound by borders. As public goods, they will not diminish through dissemination, but more rather will enrich the lives of all those who bask in it.

“Seek knowledge, even as far as in China.” Prophet Muhammad (PBUH).

Aren't We Going Home?

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light. -- Dylan Thomas

"Aren't we going home?" The question,

Poised, like the crucifix above the double doors,

Blesses the bright room, still. Bare walls forebode woe, and

Squeaky green linoleum floors keep a grip on my sanity,

While you offer one last paternal advice - from man to man.

Imam Hussein arrives on the 11th hour; prayer beads in hand,

Followed by fertile lungs that wail and grieve for you, incessantly.

Gentle nurse Isabel sobs at your last joke.

"Aren't we going home?"

Delirium takes over – you snarl at loved ones,

As they try to feed you gruel, through chapped lips.

Your nomadic days return; spear raised at the menacing lions,

"Yur! Yur!" Enflamed you yell at the inevitable, the invincible.

Alas, in a crowning effort, you raise your torso, bewildered:

"Aren't we going home? "